Figure 8.1 Inspired by Jacques-Louis David’s famous portrait of (a) Napoléon Bonaparte crossing the Alps in May 1800, (b) Venezuelan artist José Hilarión Ibarra depicted the liberator Simón Bolívar on horseback in Equestrian Portrait of Simón Bolívar, in about 1826. (credit left: modification of work “Napoleon Bonaparte crossing the Alps at the Grand Saint-Bernard” by Château de Malmaison/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit right: modification of work “Equestrian portrait of Simón Bolívar” by Unknown/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

In the late eighteenth century, new ideas of freedom spread throughout the Americas, raised by the Declaration of Independence in the former British American colonies in 1776 and by the French Revolution of 1789. These principles, combined with poor conditions for a majority of people in French, Spanish, and Portuguese America and a growing distrust of monarchy, soon led to revolutions against colonial authorities. In the first three decades of the nineteenth century, most European American colonies gained their independence. While each revolution was unique, all were connected to the broader trend of using nationalism to oppose unequal power dynamics. During these rebellions, the majestic horse, a vital part of the history and mythology of power (consider Pegasus and centaurs, for example), was associated with liberators, who were admiringly depicted on their mounts to convey independence, courage, triumph, and heroism (Figure 8.1).

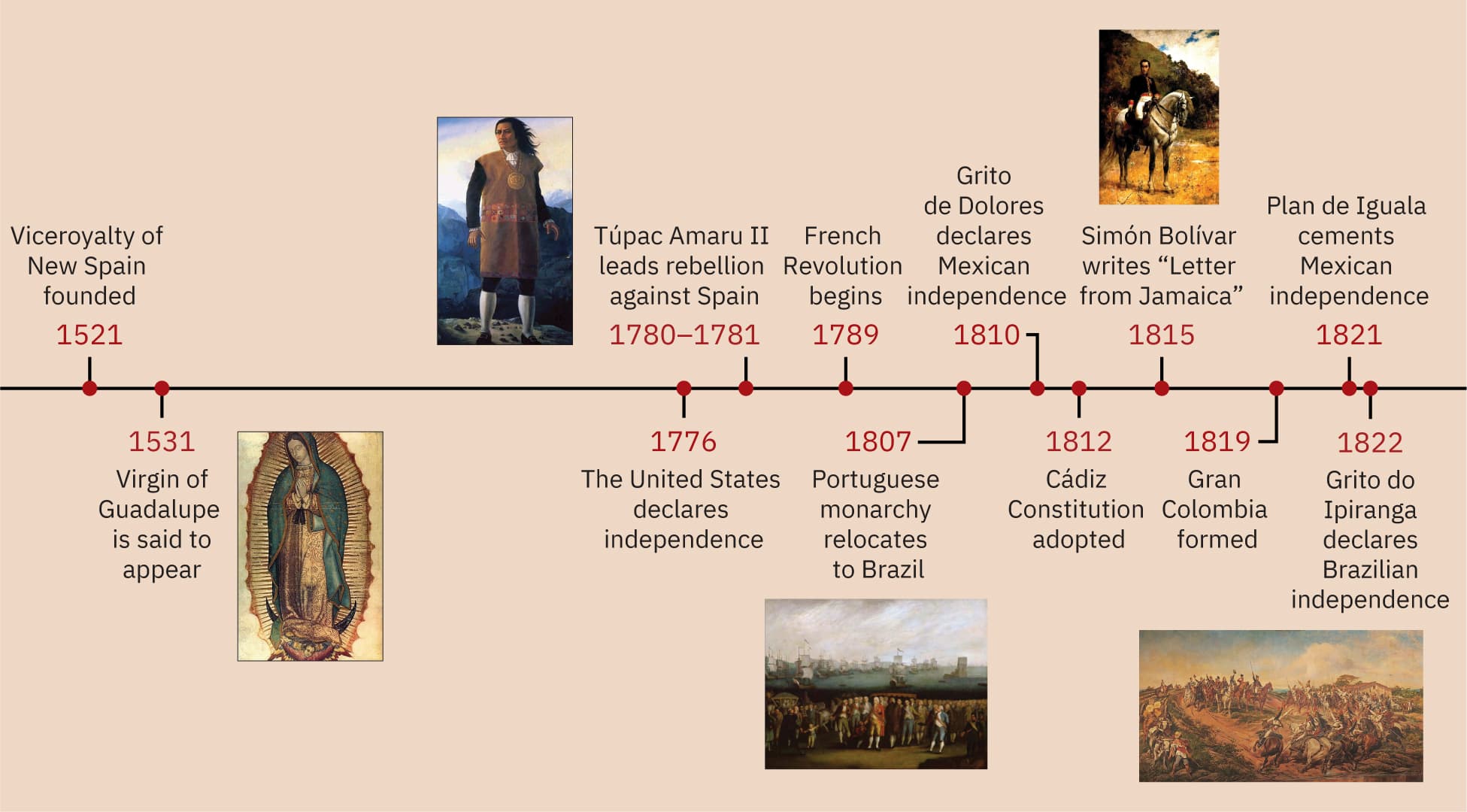

Figure 8.2 (credit “1531”: modification of work “Virgin of Guadalupe” by Unknown/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit “1780–1781”: modification of work “Portrait of Túpac Amaru II” by Unknown/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit “1807”: modification of work “Embarkation of the Portuguese Royal Family” by Itamaraty Historical and Diplomatic Museum/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit “1815”: modification of work “Retrato ecuestre de Bolivar” by Galería de Arte Nacional/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit “1822”: “Independence or Death” by Museu Paulista collection /Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Figure 8.3 (credit: modification of work “World map blank shorelines” by Maciej Jaros/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)