Figure 5.1 This intricately painted cooking vessel is from the ancient city of Harappa, in today’s Pakistan near the Ravi River. Harappan ways left an indelible mark on Indian culture. Featuring standardized weights and measures, uniform bricks, and even indoor plumbing, Harappa and the city of Mohenjo-Daro were doorways to trade, to waves of human migration, and to agriculture flowing from Egypt and Mesopotamia to the rest of Asia. (credit: modification of work “Harappa Vessel - 1-8harappanjar” by Prof Grossetti/Flickr, Public Domain)

Ancient Asia was dominated by two civilizational poles, one centered in today’s India and the other to the east, across the Asian landmass in China. Within both these zones developed impressive cities, kingdoms, and even empires whose commercial might, religion, and technology shaped the lives of Asians for thousands of years (Figure 5.1). Other Asians—traveling peoples of the steppes—acted as conduits of trade and exchange as they brought goods and ideas from one end of the continent to the other.

The same was true far to the east and the south. There, groups that became the Koreans and Japanese, as well as others who arrived in Southeast Asia via migration and trade, also carved out civilizations, smaller societies that influenced their larger neighbors in China and India. At this time, Asia was a region woven together by networks of traveling monks, nomadic peoples, oceanic and overland trade, and shared writing systems.

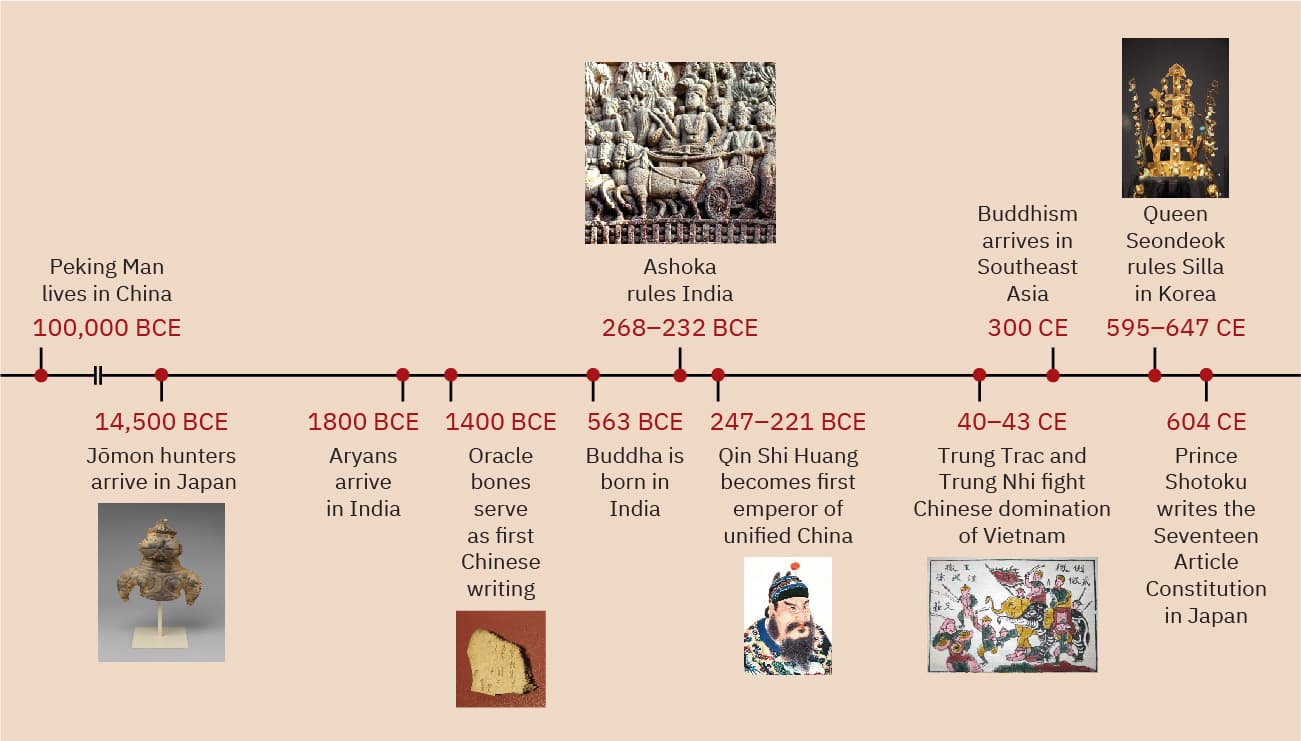

Figure 5.2 (credit “14,500 BCE”: modification of work “Dogū (Clay Figurine)” by The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975/Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain; credit “1400 BCE”: modification of work “Shang Ox Bone Oracle Bone” by Gary Todd/Flickr, Public Domain; credit “268–232 BCE”: modification of work "King Asoka visits Ramagrama" by Anandajoti Bhikkhu/Flickr, CC BY 2.0; credit “247–221 BCE”: modification of work “A portrait painting of Qin Shi Huangdi, first emperor of the Qin dynasty” by Richard R. Wertz/18th century album of portraits of 86 emperors of China, with Chinese historical notes, British Library/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit “40-43 CE”: modification of work “Hai ba trung Dong Ho painting” by “LuckyBirdie”/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit “595–647 CE”: modification of work “Gold Crown of Silla Kingsom” by Gary Todd/Flickr, Public Domain)

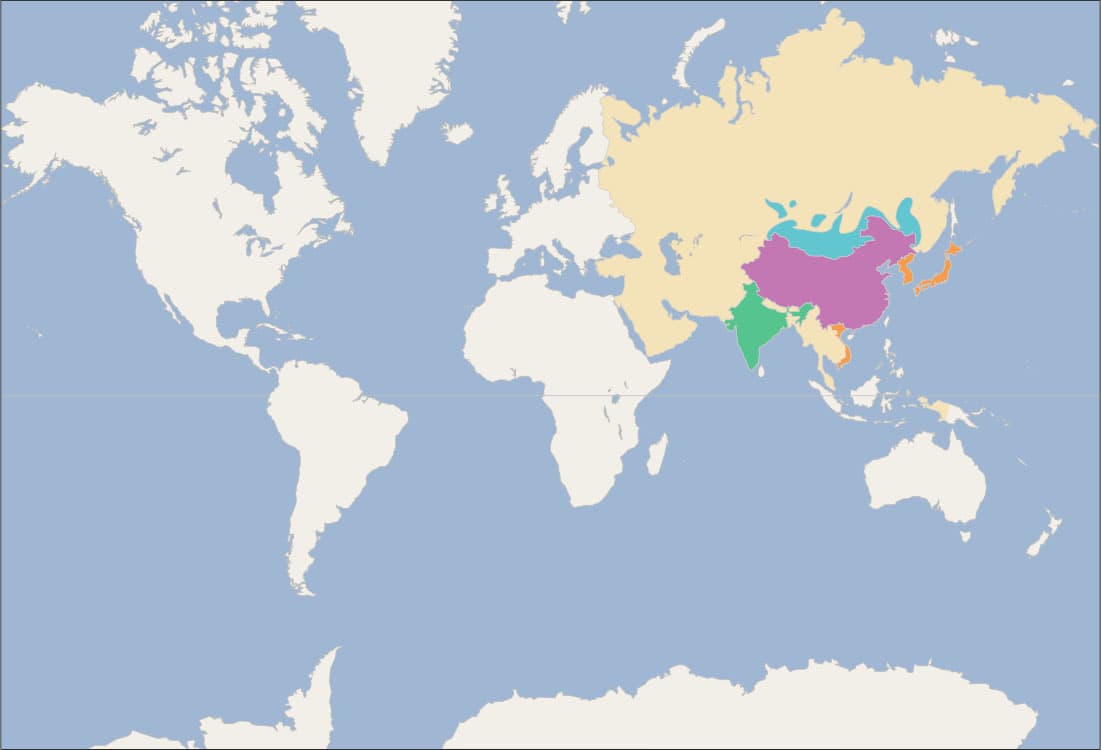

Figure 5.3 (credit: modification of work “World map blank shorelines” by Maciej Jaros/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)